Wednesday, June 13, 2012

"Why would anyone watch a scum show like Videodrome?"

For me, Videodrome only gets better with time. It is very much a product of its era; saturated with images broadcast over UHF TVs or played on VHS tapes. But don't let the nostalgia fool you; Videodrome is just as relevant today as it was in 1983. Videodrome's eerie prediction of the future (mostly concerning technology's evolution and our changing relationship to it) allows the film to remain nostalgic in look, yet novel in feel.

Campiness aside, I cannot stress how intelligent this film is. It can be seen as a critique of reality TV (the main character, Max, cannot fathom the possibility of Videodrome's signal consisting of unscripted events), of televised personalities (see my notes on Brian O'Blivion below), and of representation through television as a whole (who needs the old flesh when we can exist on TV?).

Many of these stills are of, or feature, television screens (17 of the 58 stills contain turned-on sets; 19 if you count the latex screens depicting Nicki's lips). The aesthetic is impossible to ignore, but given that we are frequently surrounded by screens in our day-to-day lives (TVs, cell phones, computers, etc), the imagery is by no means unusual. In a world where digital images are becoming a part of our reality (see here, here and here), and where film actors are commonly shown manipulating screens with a flick of their wrist (see here and here), is Videodrome really that strange by comparison? Well, yes, it undoubtedly is. However, I feel that there are obvious parallels between how easily Max could be programmed by TV, and pervasive nature of television programs.

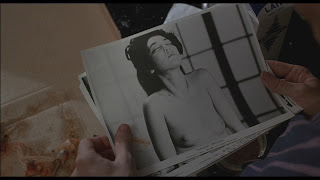

Cronenberg always has a way of complicating our notions of sex (as if they weren't complicated enough).

I always enjoy narratives that play on religion, or show other forms of representation that supplement faith. It's true that we can now watch church services on TV, instead of actually going there. But the question arises: is it our religion we worship...

...or is it our TVs?

Endless rows of cassette tapes convey the feeling of walking through a video store or archive. Here, the archive in question is of Brian O'Blivion, who continues his post-mortem existence via videotape. In the narrative of Videodrome, existing on some etheral plane - bodiless and elusive - is depicted as something strange and unnerving, but in my opinion, the only difference between the film and reality is a matter of tactility over intangiblity. Videodrome grows ever stranger with our increasing disillusionment with pre-digital technology (VHS tapes, box TVs, etc), however, millions of us are now represented online in one form or another. O'Blivion states: "Soon, all of us will have special names - names designed to cause the cathode ray tube to resonate," only now, it is the computer monitor which echoes ourselves, more so than the television screen. We create ulterior names for Myspace and Facebook, Email and IM services, for forums and blogs, as gamers and online celebrities. We have accounts and profiles floating all over the web - cutting our existence into segments - many of which, are commonly forgot about. What I find to be the most harrowing aspect of Videodrome's technological clairvoyance is that, within its narrative, these ideas seem distopian and unnatural, but when VHS tapes grow obsolete, and tangibility is replaced with the digital, the affect is suppressed and ultimately ignorable.

Fun fact: that is not James Woods sitting in the chair, but Cronenberg himself. Apparently, Woods worried that the VR device would electrocute him, so the director held his seat for him. It's funny to note how Woods' fear of technology extended beyond the film's narrative.

Out with the old, in with the new. Technology is the future and the future is now. "Death to Videodrome! Long live the new flesh!"

Labels:

1983,

Cronenberg,

David,

Flesh,

Live,

Long,

New,

TV,

Videodrome

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment